CONTROLLING TIME

THE ART OF THE ESCAPEMENT

The greatest artisan wristwatch of the 21st century, inspired by history’s greatest watchmakers.

The Lever Escapement

The escapement is the heartbeat of any mechanical timepiece: in its tick-tock oscillations, energy released from the mainspring is divided into tiny, regulated increments that govern the turning of the hands. In other words, it is where energy is turned into precise timekeeping.

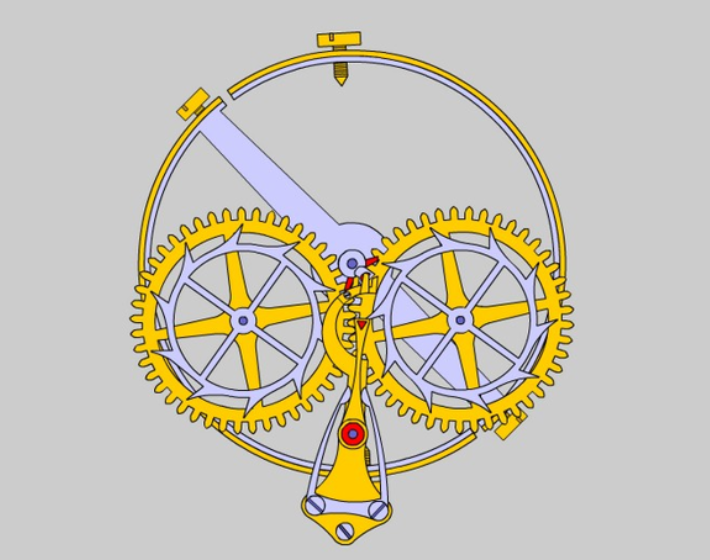

In the classic Lever Escapement (found in almost all mechanical watches), the gear train carries power to an escape wheel; a pallet fork, governed by an oscillating balance wheel, unlocks the teeth of that escape wheel, which allows the gear train to advance incrementally, turning the hands. The Lever Escapement is robust, reliable and mechanically straightforward, but its Achilles heel is friction: lubricants are needed to alleviate this, but can eventually degrade and clog the parts. The holy grail of escapements, then, is one without friction.

Breguet’s Natural Escapement (1789)

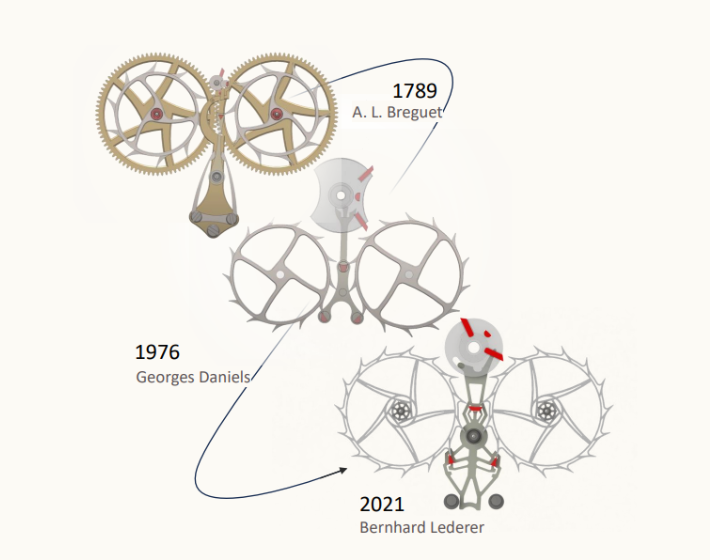

The lubrication problem was much worse in Breguet’s day, when basic oils would get horribly congealed. Breguet’s proposed solution was the Échappement Naturel, or Natural Escapement. It had two escape wheels instead of one, and no pallet fork mediating between the wheels and the balance: the escape wheels, locked and unlocked by a pivoted detent, delivered a frictionless ‘natural’ impulse directly to the balance, in each direction.

The Natural Escapement was more efficient and required no lubrication; but it was complex to build and consumed far more energy – Breguet soon abandoned it, but the sophistication of its concept continued to beguile watchmakers.

.png)

Daniels’ Independent Double-Wheel Escapement (1974)

In the late 20th Century, Dr George Daniels rose to prominence as watchmaking’s greatest modern innovator. Daniels, who had authored the definitive book on Breguet’s watchmaking, determined to solve the shortcomings of the Natural Escapement. Whereas in Breguet’s formulation the escape wheels were geared to each other, one driving the other, Daniels separated them: he designed a separate gear train and mainspring for each, meeting in a single escapement. Daniels’ Independent Double-Wheel Escapement was precise, efficient and hugely elegant in its symmetry. It was also fantastically complex to build, and vulnerable to shocks. Whilst Daniels would use it for his pocket watch masterpieces including two astronomical ‘Space Traveller’ creations, it was too bulky, too complicated and too impractical a mechanism for the demands of a wristwatch.

AN EVOLUTION IN HOROLOGY:

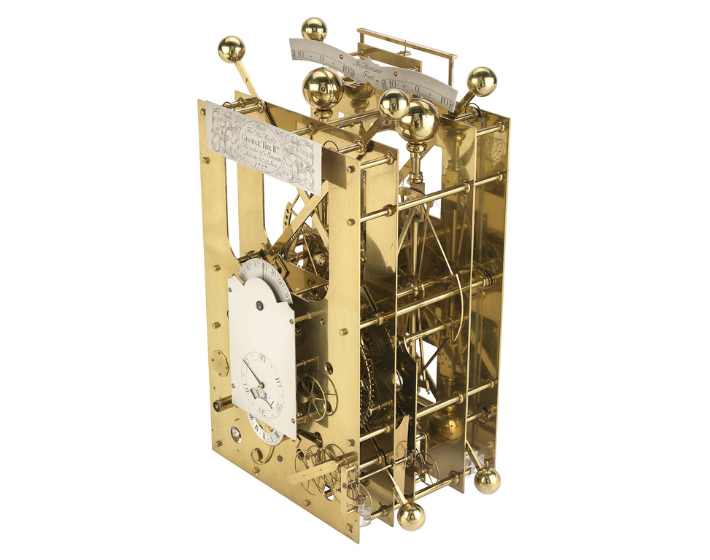

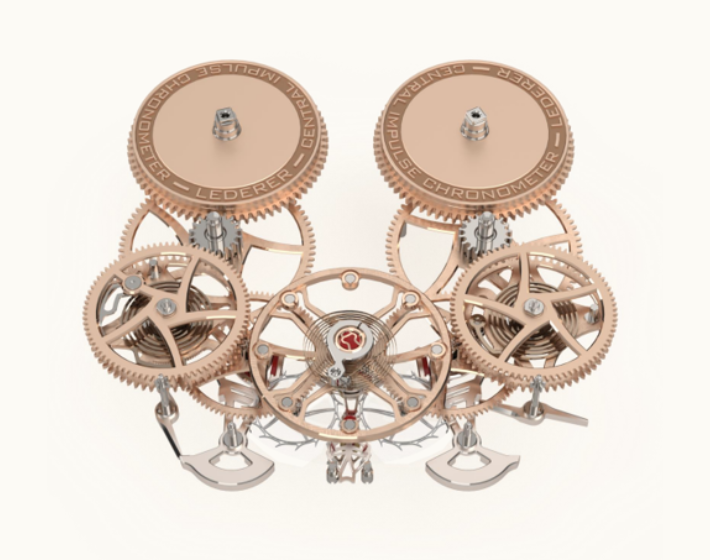

THE CENTRAL IMPULSE CHRONOMETER

With Bernhard Lederer’s Central Impulse Chronometer, the challenge of realising the Independent Double-Wheel Escapement in a wristwatch is spectacularly met. Not only is it intended for every-day wear, but in Lederer’s hands the escapement is dramatically improved and transformed. His innovations are not simply theoretical: each watch is tested and certified as a chronometer – meaning superlative chronometric performance ¬– by both the Controle Officiel Suisse des Chronometres (COSC) in Switzerland, and the historic observatory at Besançon in France.

So how has Lederer improved on the work of Daniels and Breguet?

Constant Force

As with the Daniels Independent Double-Wheel Escapement, the Central Impulse Chronometer features two independent gear trains, two mainsprings and two escape wheels. To this, Lederer adds a crucial further element: two remontoir d’égalité mechanisms, one for each gear train, to even out the flow of power to the escapement.

The remontoir was an invention of John Harrison, the celebrated 17th century inventor of the marine chronometer, who first installed it in his H2 clock of 1739. In any timepiece powered by a mainspring, the energy delivered can vary as the spring unwinds. The remontoir counters this: it features a tiny spiral hairspring that’s wound up every few seconds by the mainspring, before delivering exact parcels of energy – what’s known as ‘constant force’ – to the escapement, buffered it from any variations in the mainspring’s energy release.

A Revolutionary Anchor

At the centre of the escapement is the ‘anchor’: the linear component, or detent, that serves as the interface between the escape wheels and the oscillating balance. Through years of research, Bernhard Lederer has refined the design of this anchor, including the precise geometries of its multiple pallet stones, to optimise the moments of contact with the escape wheel teeth. It is in this revolutionary component that the Central Impulse Chronometer reaches a zenith of horological sophistication: limiting friction, preserving longevity, negating the impact of shocks and movement, and impulsing the balance at the mathematically perfect moment for precision and efficiency.

Conquering Inertia

The key escapement components are made from titanium instead of more traditional steel. Titanium is considerably lighter than steel, stiffer and with a much lower inertia, making it much more energy-efficient, and able quickly to restart after the kinds of shocks and jolts that are inevitable in a wristwatch.

Together with a 3 Hz oscillating frequency – as compared to the more stately 2Hz frequency of the Daniels escapement – these innovations ensure absolute precision and rate stability, even when shocks or abrupt movements impinge on the mechanism. Such jolts momentarily lower the amplitude of oscillations, and throw moving parts minutely off-kilter; the Central Impulse Chronometer minimises such impacts.

Discover The Central Impulse Chronometer

Watch CLP Page

Contact us